Quit: A Framework for Giving Up

Lessons from Annie Duke's new book on when to pivot or cut your losses.

If I had to pick the most universally admired character trait, I’d bet on grit.

From an early age, we teach kids to “never give up” and tell them that “winners never quit.” There are literally thousands of children’s books and classroom posters about perseverance. And as we get older, we’re inundated with real-life stories of grit - whether it’s Michael Jordan making the NBA after being cut from varsity, or J.K. Rowling getting rejected a dozen times before finding a home for Harry Potter.

It’s unquestionably important that we teach kids to stick with things, especially when they get difficult. The value of grit has been well articulated - it’s a major predictor of success across fields.

But we largely neglect the important flip side of grit: knowing when it’s time to quit. For every famous athlete, actor, and author, there are thousands of people with the same ambition and hustle who never made it. This applies to any initiative - whether it’s a startup, relationship, side project, or job. Sometimes, it’s just not going to work out. When do you cut your losses and move on?

I think this question is particularly important for high achievers and people who are naturally gritty. If you’re in this group, you’ve probably gotten where you are by being persistent. But there’s a fine line between perseverance and stupidity. At some point, it’s not worth stubbornly pursuing something if the expected value (potential outcomes * probabilities) is negative and you are forgoing better opportunities.

I found Annie Duke’s new book Quit to be enormously helpful in thinking about this. Annie is a former pro poker player, and she now studies behavioral science - making her the perfect person to write on this topic (knowing when to fold is one of the keys to success in poker).

I’ll summarize my learnings from her book in three sections: (1) knowing when to quit; (2) holding yourself accountable; and (3) navigating your next steps. These lessons are applicable to anyone pursuing a goal - personal or professional - but most of the examples I use are career-related.

Knowing When to Quit

Most of us hate the idea of quitting, so we delay this decision until it’s beyond obvious - we need flashing red lights or a message from above. But if we made the call earlier, we could have saved time, effort, and resources to deploy to something better.

Quitting at the right time requires some work in advance. Ideally, you’d do this when you initially set a goal:

Identify the hard things & plan to tackle them first. X, Google’s moonshot factory, refers to this as the “monkeys and pedestals.” If you’re trying to train a monkey to juggle flaming torches on top of a pedestal, tackle the monkey (the hard part) first. Don’t waste months crafting the perfect pedestal, only to realize that training the monkey is impossible.

If you want to launch a newsletter, don’t start by evaluating all of the publishing options and designing your logo. Figure out if there’s a topic you’re excited to consistently write about + whether you have an interesting take.

Set kill criteria. Pre-commit to cutting your losses with criteria to kill the deal / project / goal. This should include a state and date - if you don’t achieve X and Y by A date, you’ll pivot to something else. The pre-commitment is important here, because it’s hard to make the call to quit when you’re in the middle of something and don’t want to feel like you’re taking a loss or that you’ve wasted time on it.

A few examples of kill criteria:

“I’m applying to 25 PM jobs. If I don’t make the final interview for at least two in the next six weeks, I’ll widen my aperture to other roles.”

“My startup needs to sign five beta customers this quarter. If we don’t hit that bar, we’re going to re-evaluate the target audience and feature set.”

“To make YouTube worth pursuing, my audience has to grow. If I can’t add 1,000 subscribers in the next month, I’ll pivot to other channels instead.”

Schedule time to re-examine the expected value of your goal. When you set a goal, you’re choosing the path that has the highest expected value of your options (based on what you know). This expected value may change if the circumstances or your preferences evolve - which is why you need to check in regularly and be honest about whether it’s still your best choice.

If your goal is to get promoted at a startup, some of the things you re-evaluate quarterly might include: is the company gaining commercial traction? Have you been able to raise funding? Do you still believe in the mission?

Holding Yourself Accountable

You’ve gone through these steps, and your rational brain knows that it’s time to quit. But emotionally, you hate the idea of giving up or being perceived as a failure. The idea of trying one more thing or giving it “just a few more months” is attractive.

How do you follow through on your kill criteria and make the tough choice to move on?

Have a “quit coach.” Find someone who can provide an outside perspective on the decision - this person needs to care about your long-term interests and be willing to be honest with you, even if it hurts. Their role is to hold you accountable to your kill criteria (or adjust them if needed) and to point out when you are behaving irrationally.

The book has a great chapter on how legendary angel investor Ron Conway plays this role for startups struggling to find product/market fit - and the First Round Review goes deeper on this here.

Don’t allow an endless cycle of waiting. Waiting is compelling because it feels like you’re delaying the decision until you collect more data. This sounds responsible, and allows you to postpone the pain of quitting. But it can become a slippery slope. Will you ever have enough data? Remember that choosing to stick with the status quo (for now) is a decision - and you’re forgoing potentially better options every day you don’t move on.

Explore backup plans. Quitting is particularly hard when you feel trapped in your current choice and don’t have good alternatives. For this reason, Duke suggests always being open to new options, and exploring new interests as a side project. Even if you aren’t looking for a new job today, you may want to take a call with the recruiter and start building your own brand / developing thought leadership.

If you’re a startup founder, this might not resonate - you’re fully committed to your company and don’t have time for side hustles! But this may be a helpful framework for your company. If you’re struggling to find product/market fit with your current product, can you have a small team spend time exploring a new product or features that might work better?

Moving Forward

You’ve made the call to quit, and executed the decision. But you can’t stop feeling bad about it - how do you know that you made the right choice. Are you a quitter now?

Remind yourself of the costs of not quitting. Even if they aren’t widely shared, there are many stories of people who wish they had quit something earlier. Quitting too late wastes your time, energy, and resources, and may keep you from doing something better (opportunity costs are real!).

The book highlights the story of Andrew Wilkinson, who spent years and $10M of his own money building an Asana competitor called Flow. While Asana raised hundreds of millions of dollars and built a superior product, Wilkinson doubled down on Flow and refused to quit. He now wishes he had stopped “burning money” earlier and listened to the people who told him to give up.

See the opportunity in doing something new. On the flip side, quitting frees you to pursue a new direction - and it may be amazing! Once you’re no longer operating under the constraints of making your current product / job / relationship work, you may discover something much better.

Slack is the iconic example here. It started life as a game called Glitch - but a year after launch, CEO Stewart Butterfield made the call to shutter the game and go all-in on building the company’s internal productivity tool. The decision confused many investors at the time, but it paid off when this tool eventually became Slack.

Give yourself time to develop a new identity. One of the hardest things about quitting is feeling like you’re losing your identity - especially if you’ve done something for a long time and are known for it. It can be scary to move on. What if you aren’t as good at whatever you do next?

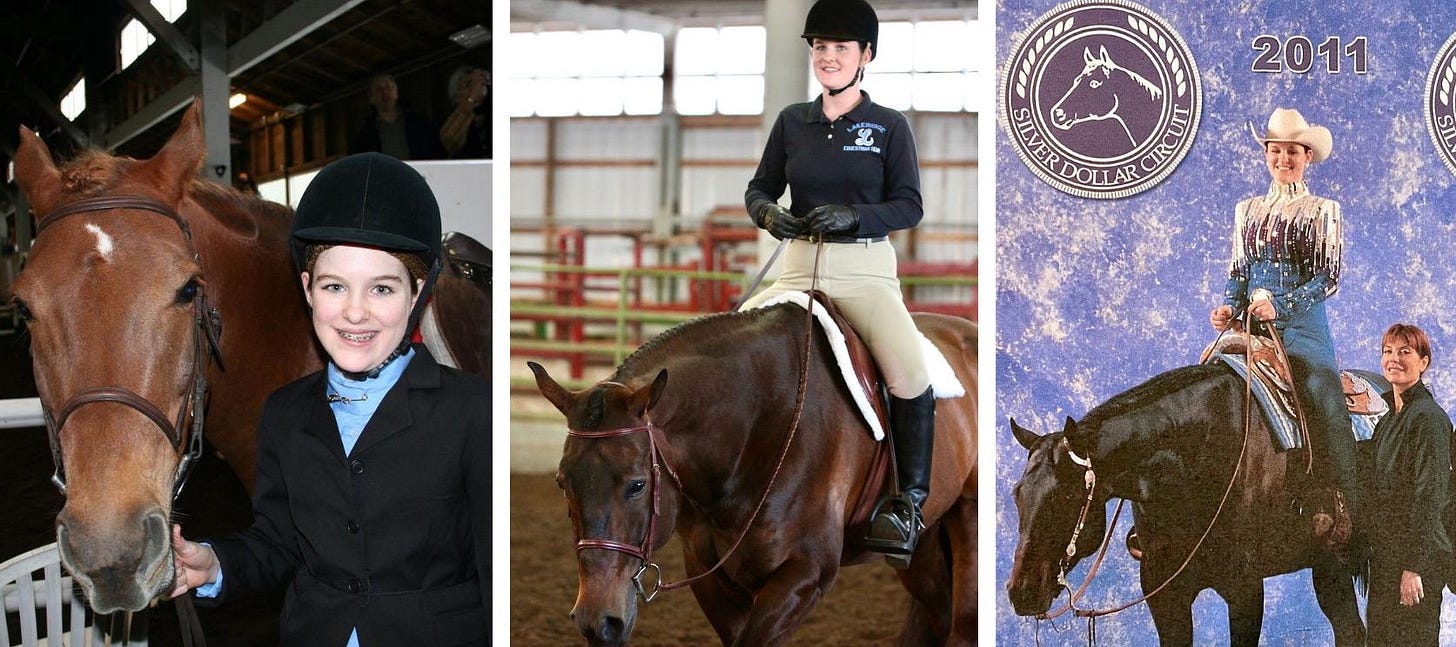

I’ve personally experienced this. I grew up riding horses, and by high school I was doing it very seriously - traveling around the country to show, winning state titles, and spending my weekends living in a trailer to train (long story).

When I went to college, it seemed like a foregone conclusion that I would keep riding on the school’s equestrian team. But when I got there, I suddenly felt unsure. There were many new things to explore - did I want to spend another four years devoted to the same activity, when I didn’t plan to do it professionally?

I decided it was time to move on from the sport that I had devoted 10+ years to, which was really difficult. It felt like I was floundering for a bit, struggling to gain my footing in something new. But it paid off when I discovered a new interest: early stage startups. And that choice led me here - to a dream role in VC, and to writing this newsletter! I’m now forever grateful for that decision to quit.

I hope you enjoyed this special edition of Accelerated! If you found this post interesting, I’d highly recommend checking out the full book and following Annie on Twitter.

As a founder who recently decided to sunset our business after 4 pivots (4 different digital products) and nearly 3 years building, this really resonates. Around the time when we were considering shutting down, First Round published a Quitting whitepaper that was inspired by Annie Duke's new book too. The specific Kill Criteria point was great for accountability - we didn't prove what we needed to prove and thus it wasn't going to work. I think there's a lot of founder fear around not looking gritty enough, but reframing quitting as freeing you up to invest your time more productively is super helpful.

Good read. People praise grid, but it's always good to know when to quit. It's Concorde effect. I put this article in our newsletter.

Memo to myself: https://glasp.co/kei/p/0a7766a3b50478fd2c41